by Fred Gardner and Dr. John McPartland.

We can only imagine how people, countless thousands of years ago, discovered that a certain plant had healing properties. Maybe a woman was gathering seeds for food when a painful period began. As she stripped the seeds out of the plant’s flower tops, a sticky resin coated her hands. She gnawed a bit of the gummy substance. Soon afterward, she started feeling better.

Her friends confirmed that this was indeed a cramp-reducing plant. They began growing it on purpose. When their tribe moved on, they brought seeds to put in the ground at their next settlement. Similar discoveries must have been made many times in many groups. People came to realize that the seeds were nourishing, the resin was pain-reducing, and the stalk provided fiber for ropes and nets.

Here and there tribes began intentionally growing this especially useful plant. The specifics are lost in the mists of history, but the plant abides and is now known to botanists as Cannabis. (The Latin name for the plant is italicized, and cannabis, the product made from the plant, is not.)

Cannabis evolved long before humans did, but because no one has found Cannabis macrofossils in rocks, it is hard to say when. Two DNA studies estimate that Cannabis evolved either 21 or 27.8 million years ago. Fossilized pollen identified as Cannabis dates to 787,000 years ago in southern Siberia.

Younger pollen, about 125,000 years old, has been extracted from a Siberian bog. Neanderthal bones from the same date were found in a cave 30 miles away. Some time after Homo sapiens migrated into the area 40,000 years ago, we forged a partnership with the plant.

“Hemp followed man naturally,” wrote Nicolai Vavilov, the great Russian plant scientist, “keeping near his dwelling places, settling on rubbish and everywhere the soil was manured.” Hemp’s camp follower” image was popularized by Edgar Anderson, a well-known botanist at Harvard University and the Missouri Botanical Garden.

At some point people began selecting the plants with the features they appreciated for cultivation—tall stalks, big oily seeds, or healing, psychoactive resin. Vavilov, Anderson, Carl Sauer, Andrew Sherratt, and Carl Sagan have linked the origins of agriculture to our ancestors’ efforts to grow more useful Cannabis. Sauer proposed that agriculture was developed by people living in fishing communities alongside rivers and lakes (the habitat of “ditchweed”) who began cultivating the plants as a source of fishing lines and nets. Nobody knows the exact where and when.

Cannabis growing in the Rif Mountains, Morocco

Classification

Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus formally described Cannabis sativa in 1753. Thirty- two years later Jean Baptiste Lamarck identified Cannabis indica as a second species. Experts continue to debate whether they should be classified as separate species or as separate varieties of one species. Extant populations of a possible third species, Cannabis ruderalis, may be a wild-type relic that descended from the ancestor of C. sativa.

Then came That ’70s Show, when Cannabis taxonomy became embroiled in the US legal system. The ethnobotanist Richard Evans Schultes, a defense witness, asserted that narcotics laws referred to C. sativa, whereas the accused possessed C. indica, which was statutorily overlooked and technically legal. Ernest Small, a taxonomic botanist, argued for a single species on behalf of the plaintiffs.

Unfortunately, Schultes and his colleague Loren Anderson made subtle shifts in Cannabis taxonomy that departed from the original concepts of Linnaeus and Lamarck. They included drug plants as well as fiber type plants within C. sativa. (We now know that the drug plants are rich in 9-tetrahydrocannabinol or THC, and the fiber-type plants are rich in cannabidiol or CBD.) Linnaeus’s C. sativa specimens were examined by William Stern in 1974 and found to be “old cultivated hemp stock of northern Europe”—rope, not dope— CBD-dominant plants.

Conservationist and hemp activist David Bronner, president of Dr. Bronner’s Magic Soaps, inspects a field of industrial hemp in Colorado, 2013. See www.drbronner.com for more information.

Schultes and Anderson delimited C. indica to plants that Schultes saw in Afghanistan. Thus they characterized “indica” as short, densely-branched plants with broad leaflets, and “sativa” along the lines of Lamarck’s species— tall, laxly branched, with narrow leaflets. They spawned the vernacular taxonomy of “sativa” and “indica” that is in use to this day. With burgeoning interest in high-CBD plants, some of which are C. sativa in the Linnaean sense, the vernacular taxonomy has become truly muddled.

Botanist Karl Hillig segregates these populations: C. sativa represents CBD-dominant plants from Europe, either cultivated (C. sativa hemp biotype) or wild-type (C. sativa feral biotype).

C. indica represents THC-dominant plants from Asia, either Lamarck’s plants from India—C. indica NLD (“narrow leaflet diameter,” known as “sativa” in the vernacular) or plants from Afghanistan— C. indica WLD (“wild leaflet diameter,” the vernacular “indica”).

Naturalists Robert Clarke and Mark Merlin adopted Hillig’s system and expanded it. Examining the worldwide distribution of Cannabis plants—wild, cultivated, and feral (once cultivated, again wild)—these experts conclude that:

Narrow-leaf hemp, C. sativa, subspecies sativa, was cultivated predominantly in Europe.

Broad-leaf hemp, C. indica, subspecies chinensis, was cultivated in China, Korea, Japan, and Southeast Asia.

Narrow-leaf drug plants, C. indica, subspecies indica, were cultivated in South and Southeast Asia and the Middle East.

Broad-leaf drug plants, C. indica, subspecies afghanica, were cultivated in Northern Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Note that the widespread interbreeding and hybridization of narrow- and broad-leafletted plants has made the application of these terms botanically imprecise in many cases.

Medical Use before the Modern Era

All the famous Old-World cradles of civilization put cannabis to medical use—China, Mesopotamia, Greece, India, and maybe Egypt. The Scythians, a tribe of migrants who inhaled cannabisinfused steam for ritual purposes, migrated out of their Siberian homeland around 800 BC. They lacked a written language, but their word for Cannabis has been reconstructed as kanab, kanap, konaba, or kannabis. The Scythians influenced civilizations in China, India, and Mesopotamia at the cusp of history.

Physician and historian Ethan Russo has visited a tomb in the Yánghai burial ground that contained nearly a kilo of cannabis. It was crudely manicured— flowering tops, leaves, and seeds, and no stems. The grave did not contain hemp fiber. It dates to 766–416 BCE. Scythians are buried nearby. Yánghai lies in the Turpan Basin, now part of China.

The ancient Chinese knew cannabis as “má.” Their pictogram for má represents two plants hung upside down to dry. Combining má with the character yào (drug) means “narcotic” or “anaesthetic.”

The legendary physician Shénnóng writes extensively about má in his Daoist-flavored medical text, Shénnóng Ben Cao Jing (also known as Pen Ts’ao Ching). He warned, “Taking much of it may make one behold ghosts and frenetically run about. Protracted taking may enable one to communicate with the spirit and make the body light.” Shénnóng supposedly lived about 4000 years ago, but the man’s legendary existence went unmentioned until about 130 BCE.

The Scythians entered history when they invaded Mesopotamia during the reign of King Sargon II (722 705 BCE). After the Scythians invaded Assyria, a new word appeared in Neo-Assyrian cuneiform. The word, which means “hemp,” transliterates as qunubu or qunnabu. The word appears in contexts that hint of use by shamans, which strengthens the Scythian connection.

The Chinese pictogram “má” represents cannabis—two plants hung upside down to dry.

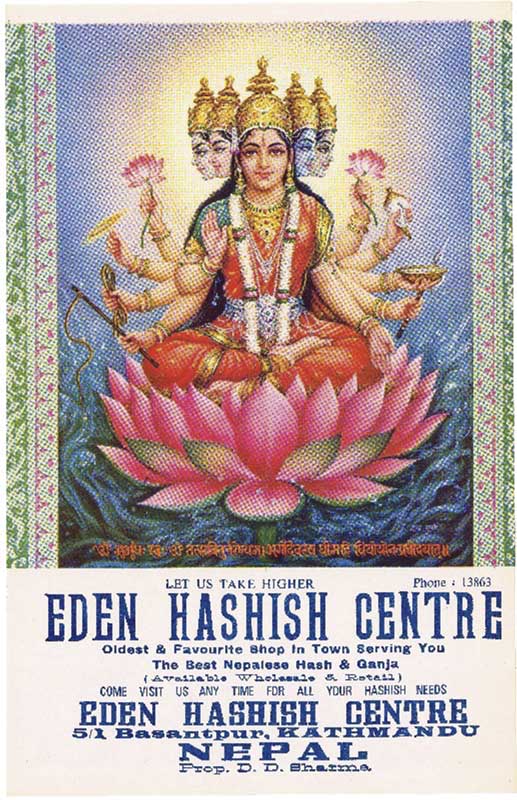

Hindu deity Shiva has long been associated with cannabis.

Herodotus, the Greek “father of history,” wrote extensively about the Scythians around 440 BCE. Herodotus coins the word xávvaßiç from a word he adopted from the Scythians. He described them using xávvaßiç for cordage and cloth, and vaporizing xávvaßiç in small tents.

In India there are more than 50 words for Cannabis and cannabis products. Archeologists working in the Ganges River basin have unearthed Cannabis seeds from at least 1300 BCE. The Atharvaveda, compiled around 900 BCE, gives the name bhånga to a plant that many experts believe is Cannabis. These dates preceded the arrival of the Scythians, whose earliest presence in the Hindu Kush may date to the 7th century BCE.

Siddhartha Gautama (ca. 563–483 BCE), the Buddha of our historic era, was an Indo-Scythian. He supposedly subsisted on one hemp seed per day during his six steps of asceticism. Practitioners of Ayurvedic medicine, India’s traditional system, recommend the herb to counter pain, insomnia, and loss of appetite.

The Egyptian hieroglyph šmšmt has been interpreted as Cannabis. The word appears in the Pyramid Texts of 2350 BCE, “the cords (or ropes) of the šmšmt plant.” However, flax and not hemp was the primary fiber crop of ancient Egypt. Other authors interpret šmšmt as Corchorus olitorius, a fibrous herb whose leaves are eaten and used medicinally in Egypt. The word also resembles šmšm, the Arabic word for sesame. Good evidence of Cannabis in Egypt begins in the Roman era.

Noted Polish anthropologist Sara Benet (neé Benetowa) argues that kaneh bosm (qaneh bosem) is Cannabis in the Old Testament, Exodus 30:22–25. The word is usually translated as “aromatic cane.” Moses used kaneh bosm for a sacred anointing oil. Benetowa notes “the astonishing resemblance” between Semitic kanbos and the Scythian word for Cannabis. But the Book of Exodus was composed around the 8th or 9th century BCE, and the Scythians did not invade the Land of Israel until 630 BCE. By then the Israelites had already been scattered and exiled by the Assyrians.

Cannabis is not native to the Fertile Crescent. Kanbos, which also transliterated kanbus or qannabbôs, first appears in Mishnah, written in the 1st century BC.

Given the evidence that cannabis products were widely used to treat illnesses in the ancient world, the real mystery is why it fell out of favor—a historical phenomenon that Ethan Russo dubbed “Cannabis interruptus.” Seeking an explanation, Russo cited “the perishable nature” of the historical record, and “humanity’s propensity toward constant warfare, invasion, and cultural conflict.”

It’s as if prohibitionists have always existed in every society, and from time to time they prevail over the physicians and patients who have put cannabis products to good use. One theory is that in many cultures, members of the priestly class viewed psychoactive plants as a threat to their role as proper intermediaries between the material and spiritual realms. They didn’t want people having visions and creative insights without their supervision. In modern times, prohibition of cannabis has provided an effective method of social control—a mechanism for funding and arming the police and a marker for disobedience among the citizenry.

The pattern of cannabis proving medically useful but getting banned continued in various parts of the world throughout the Middle Ages. In Islamic Egypt, according to Russo, “While many derided its psychoactive effects on the basis of a ban on intoxicants in Muslim sharia law, a begrudging acknowledgment was frequently made of its abundant medical attributes.”

An Egyptian king imposed a prohibition in the 13th century, but by the time Napoleon invaded Egypt in 1798, use of the herb was widespread and the French saw fit to impose a ban of their own. Thirty years later a French physician, Aubert-Roche, reported that during an outbreak of plague in Alexandria, cannabis alleviated fever, agitation, pain, bronchitis, and insomnia. And so the pendulum kept swinging between proscription and prescription.

Cannabis in the Medical Literature

England, like France, discovered medical cannabis via its colonies. The news was imparted by a brilliant Irishborn, Edinburgh-educated physician named William Brooke O’Shaughnessy. The British East India Company sent O’Shaughnessy to Calcutta in the 1830s. He was a young star, having already won accolades for devising an effective treatment for cholera—electrolyte replacement therapy—which would give rise to intravenous drug delivery.

In India, O’Shaughnessy observed that doctors were using “gunjah” extracts to treat a wide range of medical problems, including some for which Western medicine had no useful treatments. He studied the relevant literature, conducted animal studies, and tested the effects of cannabis on himself before treating patients. In 1839 O’Shaughnessy presented his findings in a paper published in the Transactions of the Medical and Physical Society of Bengal: “On the Preparations of the Indian Hemp, or Gunjah (Cannabis Indica).”

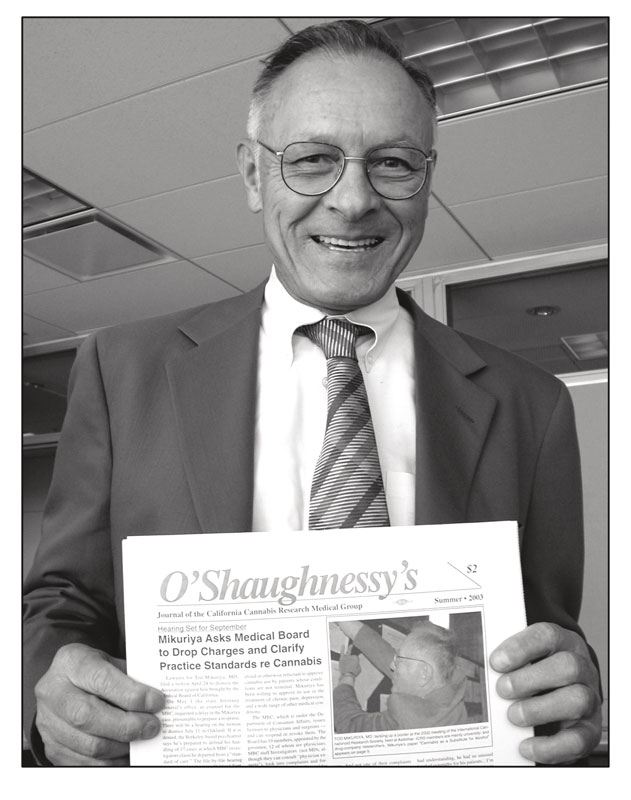

Dr. Tod Mikuriya holds the first issue of O’Shaughnessy’s, which he cofounded with Fred Gardner.

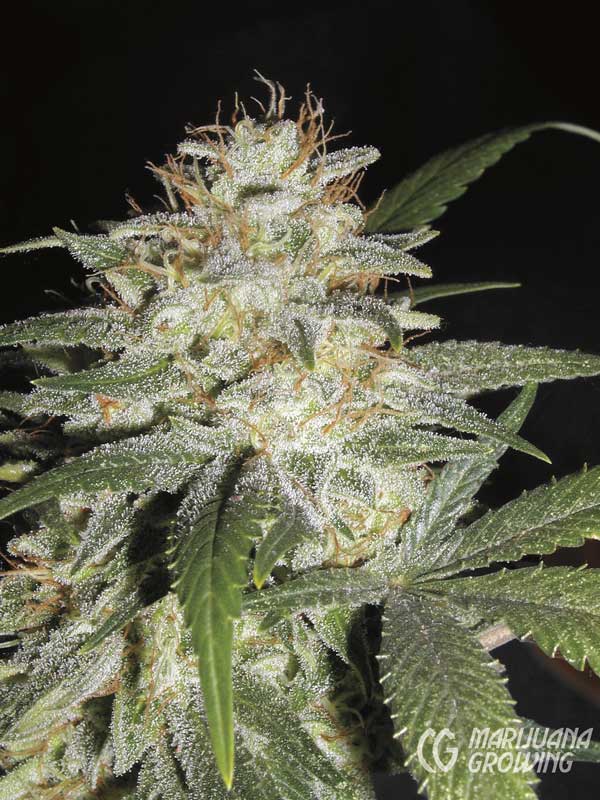

‘Sensi Star’ is a Cannabis afghanica variety with a high THC content.

At a hospital in Calcutta, O’Shaughnessy treated patients with rheumatism, hydrophobia, cholera, tetanus, and epilepsy “in which a preparation of Hemp was employed with results which seem to me to warrant our anticipating from its more extensive and impartial use no inconsiderable addition to the resources of the physician.”

O’Shaughnessy’s cannabis preparation— an alcohol extract—alleviated the symptoms of all three rheumatism patients in his clinical trial. Cannabis saved the lives of the tetanus patients (though one died of gangrene), and spared the hydrophobia patients the terrible agonies associated with rabies. It reduced diarrhea in the cholera patient. And as for the baby girl who was seen at 40 days with “infantile convulsion,” O’Shaughnessy reported, “The child is now in the enjoyment of robust health and has regained her natural plump and happy appearance.” O’Shaughnessy thought Indian hemp held greatest promise as an anticonvulsant.

In 1841 O’Shaughnessy returned to Great Britain carrying his message and, equally important, C. indica seeds of the narrow-leaf drug type. Plants of the narrow-leaf hemp type had been widely grown for fiber in Britain, but the narrow-leaf drug type was hitherto unavailable. Its arrival, and the publication in 1843 of O’Shaughnessy’s findings and recipes in the Provincial Medical Journal, enabled chemists to produce potent tinctures for use as doctors and patients saw fit. Western medicine had come to employ cannabis.

“The use of cannabis derivatives for medicinal purposes spread rapidly throughout Western medicine,” wrote Tod Mikuriya, MD, who collected and republished the early journal articles in Marijuana: Medical Papers 1839–1972. Prestigious physicians noted its benefits, including Johns Hopkins University’s William Osler, who prescribed cannabis as the first-line treatment for migraine headaches.

Back in India the British government undertook large-scale studies to investigate “deleterious effects alleged to be produced by the abuse of ganja.” In 1894 an exhaustive Report of the Indian Hemp Drug Commission concluded: “The general opinion seems to be that the evil effects of ganja have been exaggerated.”

Prescriptions for cannabis-based medicines peaked between 1890 and 1920 in the United States. Factors in the declining market share included competition from new and inexpensive synthetic medicines such as aspirin, injectable opiates and barbiturates, and a growing disdain for “crude” herbs.

Above all was the problem of inconsistent potency. As explained by the U.S. Dispensatory for 1926, “Because of the great variability in the potency of different samples of cannabis it is well nigh impossible to approximate the proper dose of any individual sample except by clinical trial. Because of occasional unpleasant symptoms from unusually potent preparations, physicians have generally been overcautious in the quantities administered.” In other words, inconsistent potency led to fear of overdose, which led to too-weak cannabis preparations! This helps explain why American consumers did not protest when the federal government banned “marihuana” in 1937.

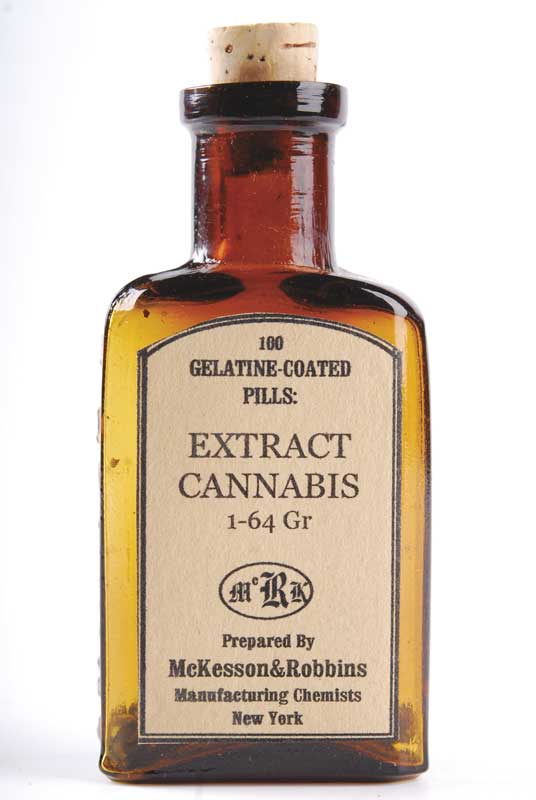

Gelatin-coated cannabis pills produced by McKesson & Robbins, one of the many US drug companies marketing cannabis extracts prior to prohibition in 1937

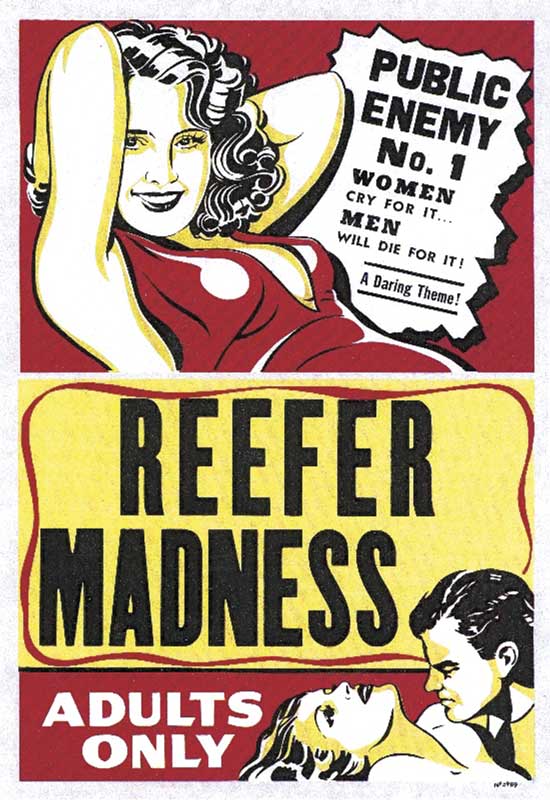

Reefer Madness is the name of a film that came to epitomize the propaganda campaign that led to federal marijuana prohibition in 1937.

The only testimony against prohibition when Congress debated it came from William Woodward, MD, of the American Medical Association. Woodward argued, “The medicinal use of Cannabis, as you have been told, has decreased enormously. It is very seldom used . . . partially because of the uncertainty of the effects of the drug. That uncertainty has heretofore been attributed to variations in the potency of the preparations as coming from particular plants used . . . To say, however, as has been proposed here, that the use of the drug should be prevented by a prohibitive tax, loses sight of the fact that future investigation may show that there are substantial medical uses.” How prescient!

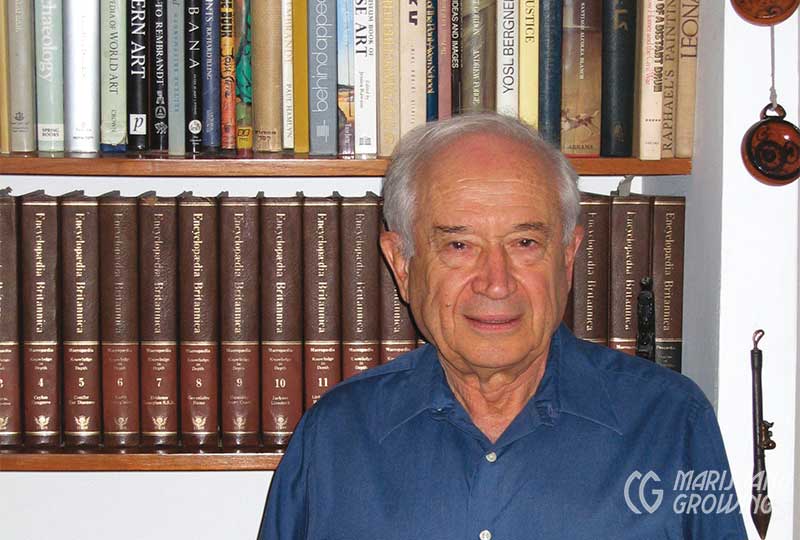

Pharmacologists Raphael Mechoulam (left) and Yechiel Gaoni worked out the exact molecular structure of THC and CBD and reported their findings in 1963 and 1964.

In 1938 New York City Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia assigned the New York Academy of Medicine to investigate the claims on which federal marijuana prohibition was based. A blue-ribbon commission of scientists and physicians concluded that marijuana is not addictive and does not lead to insanity and violent crime. Copies of the “LaGuardia Commission Report” were bought up and destroyed by agents of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics.

The end of World War II was followed by almost two decades of demonization of marijuana and individuals who used it. But by the early 1960s, developments in science and society were causing cracks in the wall of prohibition. The precise molecular structures of THC and CBD were determined in 1964 by Israeli scientists Raphael Mechoulam and Y. Gaoni. That year in New York City, Bob Dylan shared marijuana with the Beatles, presaging an era in which millions of young people around the world especially soldiers and students— would start smoking marijuana, evaluating its effects for themselves, and questioning the government’s claims.

Dr. Mechoulam popularized the term “entourage effect” to describe how compounds in Cannabis work synergistically.

Anecdotal Evidence

Those who started smoking marijuana in social settings in the 1960s,’70s, and ’80s were generally unaware that it had been widely prescribed as a medicine in the not-too-distant past. As Dr. Mikuriya put it, “It wasn’t just marijuana that got prohibited, it was the truth about history.”

Anecdotal reports of medical efficacy circulated. Seemingly everyone knew someone in the VA hospital who was using marijuana for spasticity, or had an aunt who made it through chemo thanks to the herb, or a friend who said it helped him sleep. But no physicians or researchers were tracking patients who used marijuana.

In 1990, in response to the AIDS epidemic, a Vietnam vet named Dennis Peron created the San Francisco Cannabis Buyers Club. The club provided a setting in which people who were using marijuana for medical purposes could compare notes and get a sense of their numbers. Mikuriya, seeing “a unique research opportunity,” signed on as medical coordinator and began interviewing members about their conditions, patterns of marijuana use, and results.

Peron’s remarkable club became the headquarters for activists working to legalize marijuana for medical use. They drafted “Proposition 215,” a ballot measure that would allow patients with a doctor’s approval to use cannabis medicinally. California voters passed Prop. 215 in November 1996 by a 56 to 44 percent margin—over the opposition of law enforcement and every elected official in the state, except for Terence Hallinan, district attorney of San Francisco.

Dennis Peron outside the San Francisco Cannabis Buyers Club at 1444 Market Street. In 1995 the club became the headquarters for activists planning California´s medical marijuana initiative.

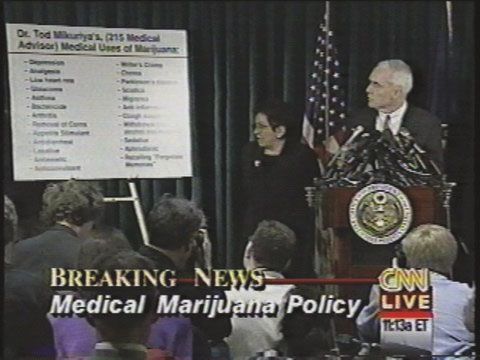

Clinton Administration officials led by Drug Czar Barry McCaffrey denounced Tod Mikuriya, MD, and threatened doctors who approved marijuana use by their patients after California voters passed Proposition 215 in November 1996.

At Dr. Mikuriya’s urging, the new law had been written to cover not just patients suffering from a few grave conditions, but also those with “any other condition for which marijuana provides relief.”

In December 1996, US drug czar Barry McCaffrey and Attorney General Janet Reno threatened to revoke prescription-writing licenses of California doctors who dared to approve marijuana use by patients. At a widely publicized press conference, McCaffrey pointed mockingly to a large chart entitled “Dr. Tod Mikuriya’s (215 Medical Advisor) Medical Uses of Marijuana.” McCaffrey said it was patently absurd that one drug could be effective in treating so many conditions. “This isn’t medicine,” he scoffed, “it’s a Cheech and Chong show.”

The American Civil Liberties Union and the reform group now known as the Drug Policy Alliance backed a suit by AIDS specialist Marcus Conant, MD, to prevent the government from carrying out its threat. The federal courts greed with the plaintiffs that doctors and patients have a Constitutional right under the First Amendment to discuss marijuana as a treatment option.

Cheech and Chong became icons for counterculture cannabis. Their movies and comedy routines made light of the supposed dangers associated with marijuana.

The Endocannabinoid System

As the legal/political conflict was playing out, vindication for Mikuriya came from scientists studying how cannabis exerts its effects. In 1990— just as the Cannabis Buyers Club was forming in San Francisco—a group of scientists met in Crete and launched the International Cannabis Research Society. The “C word” in the group’s name would be changed to “Cannabinoid” in 1998 because, as one researcher explained, “The field is moving away from the plant.”

The ICRS members were mostly pharmacologists and biochemists employed at academic research centers. Almost all received or coveted funding from the US National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), an agency whose stated goal for years has been to prove the harmfulness of marijuana. The scientists’ Holy Grail was a drug that exerts the beneficial effects of cannabis without causing any psychoactivity.

In their search for such a drug, the researchers discovered the body’s endocannabinoid signaling system compounds made in the body that activate endogenous receptors that also respond to plant cannabinoids.

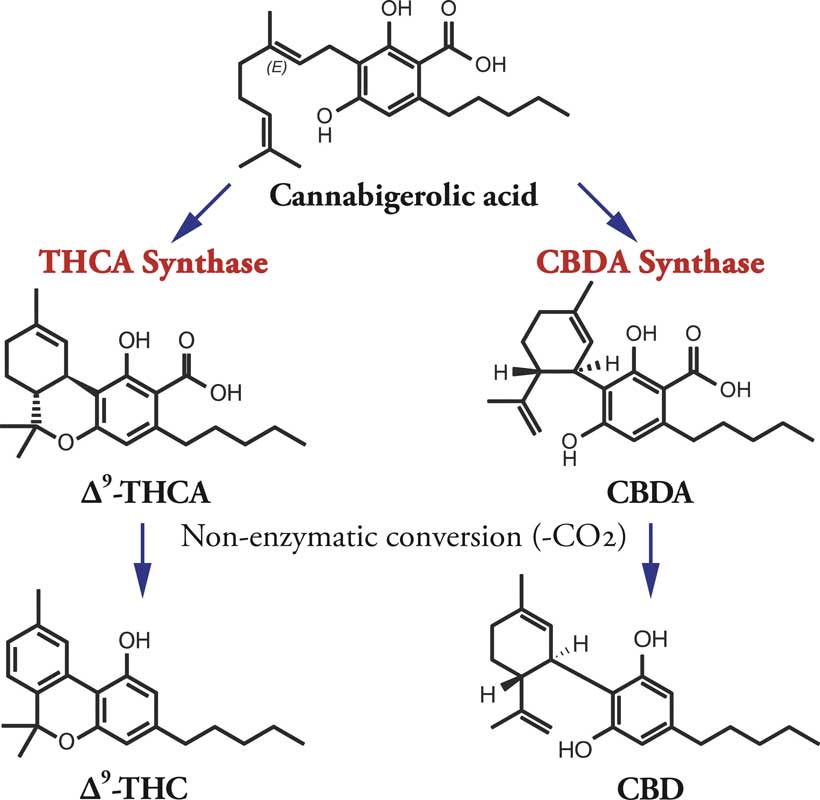

The predominant cannabinoids in Cannabis plants are CBD and THC. CBD, which is not psychoactive, predominates in hemp—plants bred for fiber and/or seed. CBD was identified in the early 1940s by Roger Adams, a University of Illinois chemist, but he did not work out its precise molecular structure.

After the discovery of endocannabinoids, CBD and THC were renamed “phytocannabinoids”—compounds found in the plant, almost all consisting of 21 carbon atoms in ring structures and side-chains, with atoms of hydrogen and oxygen attached at different points.

About 100 phytocannabinoids have been identified to date, including some biologically active ones that might have medical potential. (Some cannabinoids are fleetingly created when plant material is being analyzed, others are created by enzymes that metabolize the plant compounds.)

In addition to phytocannabinoids, the Cannabis plant biosynthesizes hundreds of chemical substances that are not unique to it, some of which are biologically active—including terpenes and flavonoids that provide smell, taste, and color. Three flavonoids have been found that are unique to Cannabis: cannflavin-A, -B, and -C.

Endogenous (“endo-”) cannabinoids are made in our bodies for sending signals from one nerve cell to another. These compounds in animals preceded the plant cannabinoids in order of evolutionary

appearance. Endocannabinoids and phytocannabinoids exert similar effects when tested on lab animals: reduction of pain, body temperature, spontaneous activity, and motor control.

Synthetic compounds that exert these effects are also classified as cannabinoids. In 1974, Eli Lilly produced nabilone, a synthetic form of THC that was marketed as Cesamet (and reintroduced years later as Nabilone). In the mid 1980s Pfizer produced a synthetic compound, CP-55940, which proved too psychoactive to market as a medicine. But unlike THC, which is not water-soluble and exerts a weak, fleeting effect, CP-55940 can be handled in aqueous solution, and binds long enough to reveal where in the body it acts. This was a great boon to research.

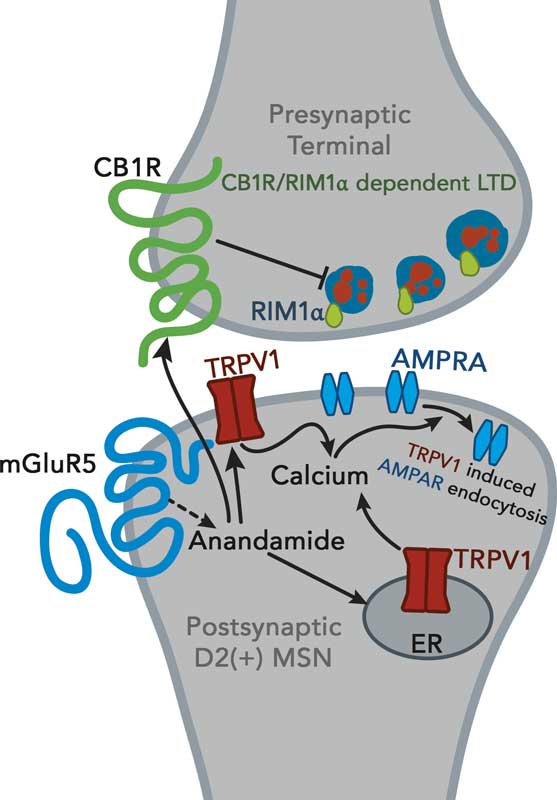

The existence of cannabinoid receptors in the brain was established in 1988 by William Devane working in the lab of Alynn Howlett at St. Louis University. The receptors are proteins embedded in cell membranes. Endocannabinoids or phytocannabinoids binding to them induce a cascade of molecular events within the cells.

These receptors, later dubbed CB1 receptors, are concentrated in the cerebellum and the basal ganglia (regions responsible for motor control, which may explain why marijuana reportedly eases muscle spasticity); in the hippocampus (storage of short-term memory); and in the limbic system (emotional control). Cannabinoids acting through the CB1 receptors play a role in the processes of reward, cognition, and pain perception, as well as motor control.

‘Sour Tsunami’, bred by Lawrence Ringo in Humboldt County, is a CBD-dominant variety. Ringo made stabilized seeds widely available to medical users.

In 1992 a second cannabinoid receptor was found in cells of the spleen, white blood cells, and other “peripheral” areas of the body. The discovery of the CB2 receptor renewed hope that effective non psychoactive drugs involving the immune system—not the brain or central nervous system—could be developed.

Also in ’92, Devane and Lumir Hanas, working in Mechoulam’s lab at Hebrew University in Jerusalemidentified the first endogenous cannabinoid a relatively simple molecule called N arachidonylethanolamine (AEA) They named it “anandamide” after the Sanskrit word for bliss. Anandamide works at the CB1 and CB2 receptors. Its effects are duplicated by THC. Also in Mechoulam’s lab, in 1994, Shimon Ben-Shabat found a second endogenous cannabinoid , 2-AG (2 arachidonoylglycerol), which also binds to both the CB1 and CB2 receptors. Unlike anandamide, which is a relatively weak agonist, 2-AG is generally a full agonist at the CB1 receptor.

Anandamide and 2-AG are unusual neuromodulators in that they work by a process called “retrograde signaling.” Conventional neurotransmitters—serotonin, dopamine, etc.— cross the gap (synapse) between a “presynapic” sending cell and a “postsyapic” receive cell. Endocannabinoids are made on demand in the postsynaptic neuron and sent back across the synapse to tell the sending cell to tone it down or speed it up.

A nerve cell sends chemical signals across a gap – the synapse- to activate a receiving cell. Endocannabinoids are made of the membrane of the receiving cell and sent back across the synapse to adjust the rate of transmission.

Plant cannabinoids have 21 carbon molecules with oxygen and hydrogen attached at various locations.

Anandamide and 2-AG restore balance— homeostasis—by inhibiting nerve cells firing too intensely and disinhibiting nerve cells firing too sluggishly. Think of a conductor facing an orchestra and directing the tempo and volume at which the instruments produce their sounds. The endocannabinoid system is the

master tone-setter of the body.

Endocannabinoids send their stay-onan-even-keel signals in systems that regulate appetite, movement, learning (and forgetting), perception of pain, immune response and inflammation, neuroprotection, and other vital processes.

The fact that endocannabinoid signaling is part and parcel of every physiological process explains why cannabinoid intake—inhaling cannabis vapor, for example—can benefit patients dealing with any of the symptoms and medical conditions on Tod Mikuriya’s infamous list. The scientists have explained what he observed and reported!

At the 2013 meeting of the International Association for Cannabinoid Medicines, Raphael Mechoulam approvingly quoted a paper that concluded “modulating endocannabinoid activity may have therapeutic potential in almost all diseases affecting humans.”

At each yearly meeting of the International Cannabinoid Research Society there has been increased emphasis on therapeutic applications and less on drug-abuse liability. Studies submitted for presentation at the 2014 meeting reflected renewed interest in the cannabis plant itself.

What the Doctors Have Learned

California’s 1996 medical marijuana initiative did not create a record-keeping system because Dennis Peron and his coauthors did not want to generate a master list of cannabis users that federal prosecutors could consult if and when they chose to. So, for all the years since, a vast public health experiment has been conducted without any state agency tracking it.

In 2006, ten years after medical use had been legalized, Mikuriya surveyed 30 doctors who had attended meetings of the California Cannabis Research Medical Group (which he had organized in 2000). He published the results in O’Shaughnessy’s, a journal he cofounded with one of us (Fred Gardner) in 2003.

Approximately 160,000 patients had been authorized to use the herb by the doctors surveyed. Unanimously, the doctors were struck by the extent to which cannabis enabled patients to reduce their intake of prescription and over-the-counter drugs. As Mikuriya put it: “Opioids, sedatives, NSAIDS, and SSRI antidepressants are commonly used in smaller amounts or discontinued. These are all drugs with serious adverse effects.”

Dr. Robert Sullivan, one of the first MDs to offer cannabis consultations in Orange County, California, reported that his patients had cut down on “opiates, muscle relaxants, antidepressants, hypnotics (for sleep), anxiolytics, neurontin, anti-inflammatories, anti-migraine drugs, GI meds, prednisone (for asthma, arthritis).” Cannabis was proving to be the anti-drug.

Reports of cannabis-using pain patients reducing their opioid intake by 50 percent jibe perfectly with studies showing that lab animals need half the opioids to achieve pain relief when also treated with a cannabinoid. Is it any wonder that synthetic drug manufacturers see the medical use of cannabis as a threat to their profit margins?

What of the alleged adverse effects, including addiction, on which marijuana prohibition rests? Dr. Philip Denney said of the ten-year survey: “Virtually none reported by patients, except contacts with the legal system. Patients are able to easily stop using cannabis in order to pass drug tests or when traveling. Overdose from edible cannabis—an unpleasant drowsiness lasting six to eight hours—is rare and transient.”

Dr. Frank Lucido responded that “decreased productivity” caused two patients to stop using cannabis. But, he added, “the overwhelming majority report that they are more productive when their symptoms are controlled with cannabis.” Employers please take note.

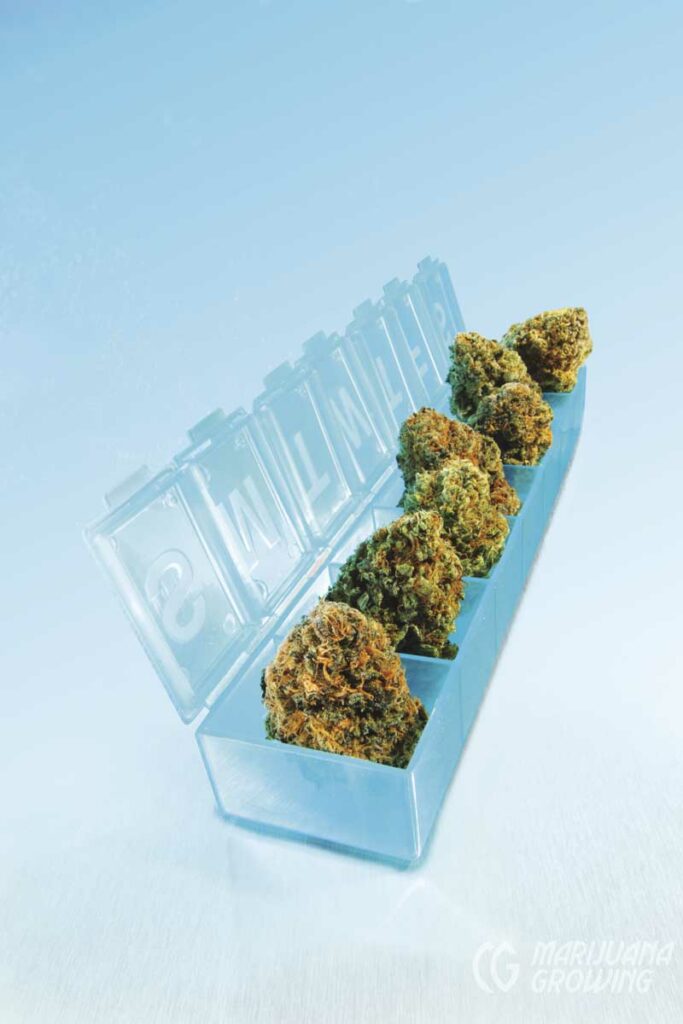

Cannabis flowers available at dispensaries have enabled patients in medical marijuana states to reduce or entirely stop use of synthetic pharmaceuticals that have adverse side-effects.

The CBD Era

The passage of Proposition 215 in California encouraged people around the world to press for access to medicinal cannabis. Multiple Sclerosis (MS) patients in England began lobbying the Health Ministry with increased urgency. In the spring of 1997, MS patients held a public meeting in London that caught the attention of pharmaceutical entrepreneur Geoffrey Guy, MD, who pledged to help them achieve their goal.

Guy observed that cannabis being used in England by MS patients and others reporting medical benefit contained substantial amounts of CBD as well as THC. The reduced psychoactivity of CBD-rich cannabis would be a key selling point when he pitched the Home Office his plan to produce a pharmaceutical-grade cannabis medicine. His company, GW Pharmaceuticals, was duly licensed to cultivate Cannabis for this purpose in the spring of 1998.

To achieve marketing approval, GW’s extracts would have to be produced with near-perfect consistency and show safety and efficacy in clinical trials. Guy’s first step had been to purchase the genetically diverse plant collection of Hortapharm, a Dutch firm founded in the 1980s by American ex-pats David Watson and Robert Clarke.

It was they who had the insight that CBD and compounds other than THC had significant effects. They traveled the globe collecting ‘land-race’ strains, some with substantial amounts of these previously disregarded ‘minor’ cannabinoids.’ Watson and Clarke also understood that the terpenoids that give Cannabis varieties their aromas exerted effects when ingested.

Sativex from GW Pharmaceuticals, a sub lingual cannabinoid spray, consists of approximately equal amounts of CBD and THC.

GW set about growing thousands of plants in sophisticated glasshouses in the southeast of England. In addition to developing high-THC and high-CBD strains, GW grew plants rich in cannabichromene (CBC), cannabigerol (CBG) and tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV) to test for medical effects. In recent years cannabidivarin (CBDV) has become a compound of interest to the company.

By 1999 GW was producing its flagship medicine, Sativex—a whole plant extract formulated for spraying under the tongue. Sativex contains approximately equal amounts of CBD and THC, plus trace amounts of all other compounds produced by the plant. GW initiated clinical trials and began providing Sativex and other cannabis extracts to researchers. Their findings, reported in journal articles and at conferences in the years that followed, suggested that CBD could ease symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, epilepsy, alcoholism, PTSD, antibiotic-resistant infections, and neurological disorders. CBD also demonstrated neuroprotective and anticancer effects. People using Sativex decreased their use of opiates and other pharmaceutical drugs. Sativex produced fewer and milder side effects than pure THC (Marinol).

In April 2005, Sativex won conditional approval from Health Canada as a treatment for pain in MS. The UK and some 20 other countries have approved Sativex for treatment of spasticity in MS. Sativex is currently undergoing clinical trials as a treatment for cancer pain in the USA and other countries.

For many years it was assumed that CBD had been bred down to trace levels in all Cannabis being grown in the USA for medical and recreational purposes. Because no analytic chemistry labs were testing cannabis samples, there was no way to assess cannabinoid content. This situation changed in the winter of 2008– 2009 when Steve DeAngelo, director of Oakland’s Harborside Health Center, encouraged two erstwhile growers, David Lampach and Addison DeMoura, to launch a lab, aptly named Steep Hill.

Harborside supplied the lab with a steady stream of samples to test for mold and to analyze for levels of THC, CBD, and CBN.

It turned out that CBD-rich cannabis was not as rare in California as experts had predicted. O’Shaughnessy’s reported that about one in 600 samples brought to Steep Hill and other labs in 2009 held 4 percent or more CBD. ProjectCBD was created to report what doctors, patients, growers, and manufacturers were learning about CBD-rich medicines.

P.S. (Post Sanjay)

In August 2013, Sanjay Gupta, MD, narrated a documentary on CNN in which he acknowledged that we all had been “systematically miseducated” about marijuana. The show provided dramatic examples of cannabis exerting beneficial effects. Most memorable was the story of a five-year old, Charlotte Figi, afflicted with a severe form of epilepsy.

Charlotte’s seizures had escalated as conventional treatments failed. Her mom in Colorado Springs and her dad, a Special Forces sergeant deployed to Afghanistan, did research online and learned about cannabis as an anticonvulsant. Paige Figi obtained buds from dispensaries, and a friend taught her how to extract oil for Charlotte. A CBD-rich variety provided seizure relief, but Paige could not get resupplied.

Wernard Bruining founded the first coffee shop in Amsterdam, Mellow Yellow, in 1972. Today he is the Dutch vanguard for medical cannabis. Visit his site, www.mediwiet.nl for more information.

Photo by Lika Bruining.

Drs. Sanjay Gupta and Geoffrey Guy at the GW Pharmaceuticals cultivation facility. GW is seeking FDA approval for Sativex (to treat intractable cancer pain) and Epidiolex (for pediatric epilepsies).

In February 2012 she met Joel Stanley, who, with his brothers, grew marijuana for their own dispensaries and had a hemp strain that worked miraculously well for Charlotte. The Stanleys renamed their plant “Charlotte’s Web” and offered to grow it in large quantities for the Figis and others in need. When Sanjay Gupta visited their greenhouse, one of the Stanley brothers pointed to a Charlotte’s Web plant and claimed, “There’s nothing like this in the world. This plant is 21 percent CBD and less than 1 percent THC.”

Fortunately, there are other cannabis plants with CBD:THC ratios greater than 20:1, and they are being grown in California and other states where it is legal to do so. Nor is it clear that the higher the CBD-to-THC ratio, the more effective the medicine. There may be an optimal ratio for treating each illness and each individual. Terpenoid and flavonoid content will influence the effects of any given cannabis-based medicine. A challenging research opportunity presents itself to doctors and patients, growers and medicine makers.

The federal Farm Bill of 2014 legalized cultivation of “industrial hemp”containing 0.3 percent THC or less for research purposes. This enabled the Stanley Brothers to grow 36,000 Charlotte’s Web plants—now bred to contain 30:1 CBD-to-THC—on 17 acres, and to redefine their extract as CW Hemp Oil. Several thousand hemp plants were also grown in Kentucky for medical use. “Industrial hemp” is providing more than food and fiber. A bill to remove CBD and hemp from the Controlled Substances Act has been introduced in Congress.

Hundreds of parents of children with epilepsy, cancer, and other serious illnesses have moved to Colorado in hopes of obtaining Charlotte’s Web. A nonprofit called Realm of Caring, cofounded by Paige Figi, counsels families who are using the Stanley Brothers’ product, maintains a waiting list of prospective clients, and acts as an educational resource. In 2014, eleven states passed bills legalizing cannabis containing minute amounts of THC. Prohibitionists see these so-called CBD-only bills siphoning support from bills that would legalize THC for medical use (as happened in Florida in November 2014). Advocates see them as a first step toward more comprehensive legislation.

Numerous companies are producing and distributing cannabis-based medicines in the USA and overseas. The boldest sell CBD-rich products through the mail and online. Although CBD remains on Schedule One of the federal Controlled Substances Act, hemp food products containing less than 0.3 percent THC are legal (and on sale at Costco).

Lawrence Ringo (left) and Jaime Carion (‘Cannatonic’ breeder, Resin Seeds) at the High Times Medical Cannabis Cup in San Francisco. Nobody did more to expedite and expand the availability of CBD-rich plants for medical use than these two men.

Federal regulators have not moved against companies importing medical products containing larger amounts of CBD extracted from hemp plants grown legally overseas. The Stanley Brothers— who were advised in 2014 against shipping Charlotte’s Web Hemp Oil from Colorado to patients in other states—now plan to grow plants in Uruguay and other foreign countries, and send the oil back to patients in the USA.

GW Pharmaceuticals is seeking FDA approval for Epidiolex, a CBD extract devoid of THC. Epidiolex was made available in 2014 to epilepsy specialists conducting Investigational New Drug (IND) programs at hospitals in the USA, involving some 200 children. More than half experienced significantly fewer and less severe seizures. About 15 percent were unhelped, and about 15 percent were seizure free. A similar pattern has been reported by Bonni Goldstein, MD, and Margaret Gedde, MD, physicians who treat hundreds of children using CBD-rich cannabis for epilepsy in Los Angeles and Colorado Springs, respectively.

Project CBD organizer Martin Lee says, “How ironic that the prohibition of cannabis, presented to Congress and a gullible public as a way to protect children from a deadly vice, is crumbling because children are in dire need of cannabis as medicine.”

The doctors group organized by Tod Mikuriya in 2000, now known as the Society of Cannabis Clinicians, had more than 100 members as of June 2014. The SCC has been headed since 2009 by Jeffrey Hergenrather, MD, a founding member. “Doctors’ and patients’ understanding of how cannabis works has advanced significantly in recent years,” he says. “Now it’s time for the medical schools to acknowledge the endocannabinoid system.”

Jason David suministró aceite rico en CBD del Harborside Health Center de Oakland a su hijo Jayden, que consiguió aliviar las convulsiones. La noticia de la mejoría de Jayden inspiró a los padres de Charlotte Figi a buscar CBD en Colorado. Foto de Braverman Productions.

Interesting links

O’Shaughnessy’s, covers the ongoing history of the medical marijuana movement.

ProjectCBD.org reports on the availability of CBD and what scientists, doctors, patients, and growers are learning about it.

The CBD Crew, a partnership between Mr. Nice and Resin Seeds, produces CBD-rich varieties.